Deer in IRELAND

Red deer

Red deer are our largest and the only native species to Ireland. They are believed to have had a continuous presence in Ireland since the end of the last Ice Age (c. 10,000 BC). At this time they roamed freely through out Ireland, however as a result of deforestation, over hunting and the Great Famine (1845 – 1847) many populations became extinct. By the middle of the 19th century the last home of the Red deer was in the woodlands and mountains around Killarney, where their preservation was due to the strict protection of the two large estates of Herberts of Muckross and the Brownes, Earl of Kenmare. It is known that at the turn of the century there were in excess of 1500 Red deer in Killarney. This declined between 1900 and 1960 to as few as 60. As a result of rigorous protection and management they have increased to 690 in the early 1990’s within the National Park.

Identification

The Red deer has a rich red coloured coat, darkening down to a greyish brown in winter. A mature stag carries a large rack of antlers, which are at peak condition in the early autumn for the rut, when they are used for bouts of sparring between rivals. A dominant animal may have 18-20 points (tines) on the antlers, although 14-16 is more common. A stag with more than 12 tines is known as a ‘Royal’. A fully-grown Red stag can stand 120cm (48”) high at the shoulder and can weigh anything up to 190kg (420Ibs). A female (hind) is smaller with shoulder height up to 110cm (44”) and a weight of up to 110kg (240Ibs).

Where Found

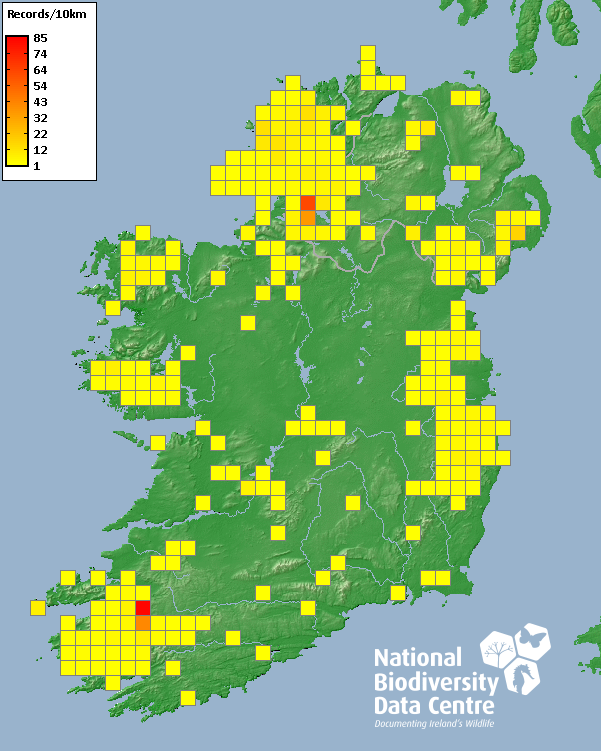

While some claims have been made, the number of wild Red Deer and their hybrids in Ireland are unknown as no national deer census have been carried out. The main deer range can be found on Torc, Cores and Mangerton Mountains with other herds in the lowland areas of the national park in Killarney, Co Kerry. These are the only native wild Red deer that exist in Ireland today. Sika deer are potentially a threat to the genetic integrity of the Red deer herd, as they are known to be capable of interbreeding. So far no cases of crossbreeding between Red and Sika have been recorded in Killarney (as has happened in Wicklow), but the situation is being carefully monitored, and a high priority is attached to maintaining the genetic purity of the native herd. Other herds can be found in the Glendalough Valley and Turlough Hill in Co. Wicklow, also wild herds exist in Glenveagh, Co. Donegal, Connemara, Co Galway and areas of Co Mayo. These are not native herds but were introduced from Scotland in the 19th Century. Red deer stags are easiest to see in late September and early October during the rut.

Characteristics

Red deer are a herd deer but group size is influenced by habitat, they form larger herds when living in open country with smaller groups in woodland areas. They are primarily grazers and will graze all year round, however they will eat heather shoots, mosses, lichens and even unpalatable mat-grass to see them through winter to the following spring. Stags grow antlers in late Spring and have a soft skin covering called velvet. Antlers will grow until late summer; the velvet dies and is – scrapped off. Neck muscles will swell, thick manes grow on the throats and aggression increases. The antlers are fully grown by late summer and will remain until they are shed in early spring. Antler size to some extent depends on age but more importantly on the deer’s health and nutrition. In the wild the best heads are found on 6-8 year old animals.

Does may breed at a year and a half, if pregnancy does not occur, ovulation (heat) will occur again in 21 days later. Pregnancy in a Doe lasts 33 weeks and fawns are born in June. It is important to note that fawns do not follow their mother for two weeks. While the mother is off grazing the fawns are left lying in cover. Such fawns are not abandoned and should not be touched or removed. Fawns may continue to suckle until the next sibling is born.

Breeding

The breeding season (rut) is in October. The timing of the rut is controlled by the length of the day. By mid September, aggression is more marked. Mature stags are increasingly intolerant of each other, and there are short chases as they attain peak condition. These animals are first to rut. Traditionally, the first roars (loud deep low-pitched call) are heard in the last week of September, signalling the commencement of the rut. Each stag is seeking to gather hinds to herd together for his harem (on average 5 hinds), he will then endeavour to possess exclusively, by marking and defending the territory over which the hinds roam. He will mate with the fittest hinds, which normally come on heat by the second and third week in October. During the rut, while the stag waits for each hind in his harem to come in season, he will wallow in peat, thresh the vegetation with his antlers, as well as roar and clash in contest with competing males. As October draws to a close, the, majority of stags have finished the rut. The priority at this stage of the year is to build up fat reserves for the winter.

Hinds may breed at a year and a half, with calves born in June. The placenta (afterbirth) is eaten by the female, to hide any sent or evidence of the birth. The calf is hidden while the hind feeds alone.

Protection and Control

Red deer are a protected game species and may only be hunted with a licence from the National Parks and Wild Life Service. Red stags may be hunted from the 1st of September until the 31st of December (no season in Kerry for stags) and Hinds may be hunted from the Ist of November to the 28th of February 28th. Hunting of Red deer is strictly prohibited in Co Kerry.

Wild Deer Association of Ireland is fully committed to the conservation of Irish Deer and the protection of habitat. The Association also offers to promote the interests of legitimate hunters and offers guidelines to same with meeting on Topical issues, Code of Conduct/ Safety, Target Shoots etc.

Fallow deer

Where Found

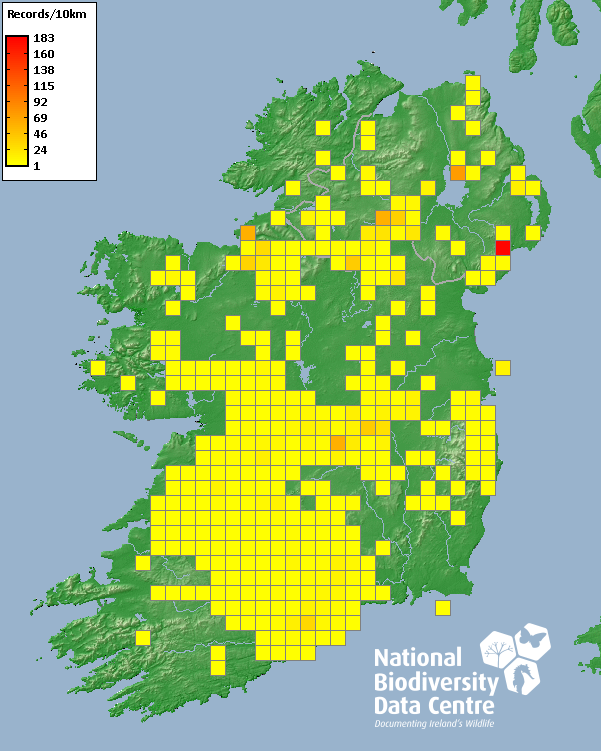

Fallow deer are our most popular park deer with over 60 herds in parks or enclosures. While some claims have been made, the number of wild Fallow Deer in Ireland are unknown as no national deer census have been carried out. Many of our now wild Fallow escaped in the early 20th century, which supplemented old wild herds introduced by the Norman’s soon after their arrival in 1169. They are now our most widespread species of deer and are found in most woodlands countrywide, both hill and lowland. Fallow have a very keen sense of smell and are acutely aware of any foreign noise. In hunted areas or where deer are disturbed it is easier to find them grazing at dawn or before dusk and one should approach carefully from the downwind side.

Fallow bucks are easiest to see in October during the rut. They tend to use the same rutting ground each year and the rutting area would have a strong musky smell with some scraping of the ground and tree bark damage.

Identification

This is the only Irish species of deer where the bucks have palmate (broad flattened) antlers. The coat coloration is quite variable including Black, White, Brown, Yellowish etc. With the exception of Black and White, the rest have a white underbelly and white rump patch with a black line surround and a black line from the top of the shoulder to the tip of the tail. Common Fallow (the most numerous) are light brown with white spots in summer and this grey and darkens in the winter. Size wise, the fallow is between the Sika and the Red. With adults bucks weighing about 100lbs or about 55kg carcass weight and Does weighting 40-45 kg live weight.

Characteristics

Fallow are a herd deer but group size is influenced by habitat. They favour a varied habitat with cover and grazing, that is mixed deciduous woodland or pine with grazing. They are primarily grazers and will graze all year round, however the will eat herbs, leaves, acorns, young deciduous shoots and farm crops (sugar beet). Bucks grow antlers in late Spring and have a soft skin covering called velvet. Antlers will grow until August, the velvet dies and is scraped off. The antlers are fully grown in August and will remain until they are shed in March and April. Antler size to some extent depends on age but more importantly on the deer’s health and nutrition. In the wild the best heads are found on 7-9 year old animals.

Breeding

The breeding season (rut) is in October. The timing of the rut is controlled by the length of the day. During the rut the bucks move into females’ area and competition for females can be intense. Fallow bucks will fight quite aggressively for dominance and may aggressively lock antlers and push or wrestle. The bucks emit sounds (groans) during the rut which is rhythmic and cough-like. Scraps and markings can be found in rutting areas which are scented by glands on the bucks face.

Does may breed at a year and a half, if pregnancy does not occur, ovulation (heat) will occur again in 21 days later. Pregnancy in a Doe lasts 33 weeks and fawns are born in June. It is important to note that fawns do not follow their mother for two weeks. While the mother is off grazing the fawns are left lying in cover. Such fawns are not abandoned and should not be touched or removed. Fawns may continue to suckle until the next sibling is born.

Protection and Control

Fallow deer are a protected game species and may only be hunted with a licence from the National Parks and Wild Life Service. Fallow bucks may be hunted from the 1st of September until December 31st and Does may be hunted from the Ist of November to the February 28th.

Wild Deer Association of Ireland is fully committed to the conservation of Irish Deer and the protection of habitat. The Association also offers to promote the interests of legitimate hunters and offers guidelines to same with meeting on Topical issues, Code of Conduct/ Safety, Target Shoots etc.

Sika Deer

Origins

Sika deer most probably originated from the Japanese Islands in north eastern Asia. One stag and three hinds were the original breeding stock for all Sika in Ireland. These were introduced by Lord Powerscourt in 1860. A few years later some Sika from Powerscourt were moved to enclosed parks in Fermanagh, Kerry, Limerick, Down and Monaghan. However our present wild deer herds mostly originated as escapees from these parks in the early 20th century during the troubles.

Where Found

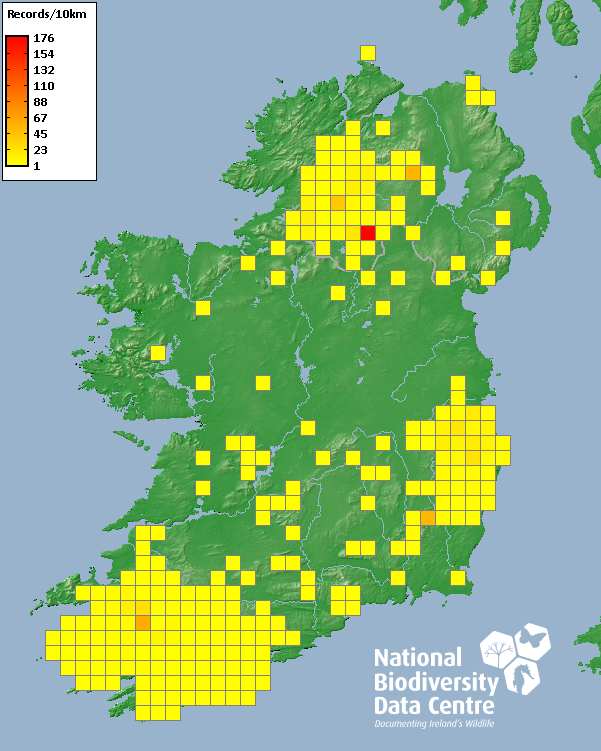

The main herds of wild Sika deer are concentrated in Kerry, Wicklow, Tyrone and Fermanagh with some establishing herds in Dublin, Kildare, Carlow, Cork and Donegal.

While some claims have been made, the number of Sika and their hybrids in Ireland are unknown as no national deer census have been carried out. It is easiest to see Sika deer when they are actively grazing, mainly at dawn or dusk. Sika are extremely shy and one should take great care to approach carefully from downwind. Sika have a preference for acid soils and will quickly establish in young pine plantation. They are opportunistic and will colonise a variety of woodland habitats with grazing.

Identification

The antlers of the stag are branched and can have up to four points on each. The rump has an almost concealed white patch with white surrounding hair. When alarmed the white rump patch is magnified and exposed, which is distinctively heart shaped. Coat coloration gets progressively lighter from the ridge of the back to the underbelly. The lighter browns of summer change to grey browns and almost black in Winter.

Sika are our smallest deer with stags up to 80cm at the shoulder and weighting 50-60kg. Adult females (hinds) are less than 70cm tall and weight 35kg.

Characteristics

Sika deer are primarily grazers but will eat herbs, heather, young tree shoots and farmed root crops as the opportunity presents itself. The mainly feed in the morning and late evening.

Group size in Sika is usually up to ten animals, consisting of females, follower offspring and non breeding males. Stags on the other hand only join the herds during the rut. Antler development in stags usually reaches it’s potential in 7-8 year olds. However at full maturity antler development is more dependant on nutrition and health than age. They will shed antlers in spring and growth starts immediately. A skin covering called velvet covers the antlers while growing and is scrapped off to reveal hard antlers before September. Like Red deer, Sika have pointed or spike like antlers, unlike the palmate of Fallow.

Breeding

Day light controls the timing of the rut which is in late September to early October. Stags can be heard either clashing antlers or emitting a ‘whistle’ which sounds high pitched at the start and ends in a low pitched moan. Sika stags will be subdued into submission by being pushed backwards. Mating areas or stands are marked by a facial scent. This is a territorial signal to other stags to keep away. Territorial rutting areas are the norm in establishing herds. However in developing populations stags tend to move to seek out hinds and then gather them together.

Hinds can conceive at one and a half years of a age and in the absence of conception, ovulate at 21 day cycles. Pregnancy last over 7 months and calves are born in early June and weaning usually occurs in spring.

Sika deer and our native Red Deer are of the same genus Serves and can interbreed. The resulting hybrids are also fertile, this is a major concern in preserving the genetic purity of both Red and Sika. There is a disagreement as to whether interbreeding only occurs in captive (penned or park) mixed herds. Interbreeding in the wild is certainly rare. Many believe that the Red and Sika herds of Killarney are still genetically pure, however most Sika-like deer in Leinster have some ‘Red’ blood.

Protection and Control

Sika are protected under the Wildlife Act 1976 and may be hunted under licence. Stags may be hunted from September 1st to December 31st and Hinds from November 1st to February 28th. Of the three Irish deer species, Sika pose as the greatest pest to forestry and agriculture. They can eat leader shoots and damage bark with their teeth and antlers. In farm land they have a liking for root crops and cereals.

Wild Deer Association of Ireland is fully committed to the conservation of Irish Deer and the protection of habitat. The Association also offers to promote the interests of legitimate hunters and offers guidelines to same with meeting on Topical issues, Code of Conduct/ Safety, Target Shoots etc.

Reeves’s Muntjac (Invasive Species)

Muntjacs, also known as barking deer and Mastreani deer, are small deer of the genus Muntiacus. Muntjacs are the oldest known deer, thought to have begun appearing 15–35 million years ago, with remains found in Miocene deposits in France, Germany and Poland.

The present-day species are native to South Asia and can be found in Sri Lanka, Southern China, Taiwan, Japan (Boso Peninsula and Ōshima Island), India and Indonesian islands. They are also found in the lower Himalayas and in Burma. Inhabiting tropical regions, the deer have no seasonal rut and mating can take place at any time of year; this behaviour is retained by populations introduced to temperate countries.

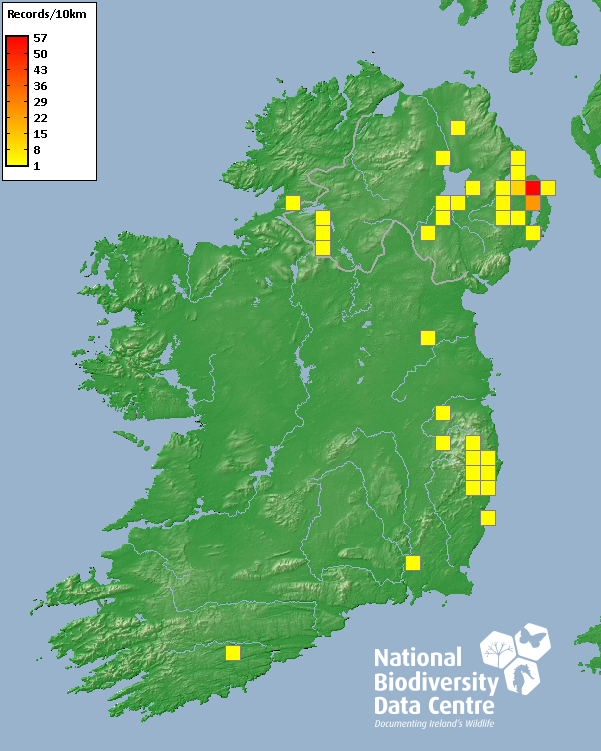

Reeves’s muntjac have been introduced to Northern Ireland in 2009; they have been spotted in the Republic of Ireland in 2010, almost certainly having here with some human assistance.

Males have short antlers, which can regrow, but they tend to fight for territory with their “tusks” (downward-pointing canine teeth).

Impacts:

- Muntjac deer destroy the understory of forests by overgrazing; act as a reservoir for diseases (bovine TB) and parasites for domestic livestock; strip bark from trees and trampling of vegetation which in turn may lead to increased soil erosion.

Irish elk

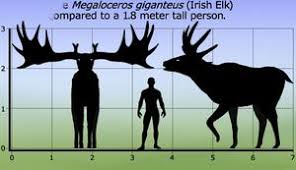

The Irish elk (Megaloceros giganteus) also called the giant deer or Irish deer, is an extinct species of deer in the genus Megaloceros and is one of the largest deer that ever lived. Its range extended across Eurasia during the Pleistocene, from Ireland to Lake Baikal in Siberia. The most recent remains of the species have been carbon dated to about 7,700 years ago in western Russia.

Although abundant skeletal remains have been found in bogs in Ireland, the animal was not exclusive to Ireland nor closely related to either of the living species currently called elk: Alces alces (the European elk, known in North America as the moose) or Cervus canadensis (the North American elk or wapiti). For this reason, the name “giant deer” is used in some publications, instead of “Irish elk”. Although one study suggested that the Irish elk was closely related to the red deer (Cervus elaphus),[10] most other phylogenetic analyses support that their closest living relatives are fallow deer (Dama dama).

Contents

1 Taxonomy

1.1 Research history

1.2 Evolution

2 Description

3 Habitat

4 Palaeobiology

4.1 Physiology

4.2 Reproduction

4.3 Life history

5 Extinction

6 Cultural significance

7 See also

8 References

9 Further reading

10 External links

Taxonomy

Research history

Skeletal reconstruction from 1856

The first scientific descriptions of the animal’s remains were made by Irish physician Thomas Molyneux in 1695, who identified large antlers from Dardistown, Dublin—which were apparently commonly unearthed in Ireland—as belonging to the Elk (known as the Moose in North America), concluding that it was once abundant on the island. It was first formally named as Alce gigantea by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in his Handbuch der Naturgeschichte in 1799, with Alce being a variant of Alces, the Latin name for the Elk. French scientist Georges Cuvier documented in 1812 that the Irish elk did not belong to any species of mammal currently living, declaring it “le plus célèbre de tous les ruminans fossiles”. In 1827 Joshua Brookes, in a listing of his zoological collection, named the new genus Megaloceros (spelled Megalocerus in the earlier editions) in the following passage

Amongst other Fossil Bones , there [are] … two uncommonly fine Crania of the Megalocerus antiquorum (Mihi). (Irish), with unusually fine horns, (in part restored)

— Joshua Brookes, Brookesian Museum. The Museum of Joshua Brookes, Esq. Anatomical and Zoological Preparations, p 20.

The etymology being from Greek: μεγαλος megalos “great” + κερας keras “horn, antler”. The type and only species named in the description being Megaloceros antiquorum, based on Irish remains now considered to belong to M. giganteus, making the former a junior synonym. The original description was considered by Adrian Lister in 1987 to be inadequate for a taxonomic definition. In 1828 Brookes published an expanded list in the form of a cataologue for an upcoming auction, which included the Latin phrase “Cornibus deciduis palmatis” as a description of the remains. The 1828 publication was approved by International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) in 1977 as an available publication for the basis of zoological nomenclature.[2] Adrian Lister in 1987 judged that “the phase “Cornibus deciduis palmatis” constitutes a definition sufficient under the [International Code of Zoological Nomenclature] (article 12) to validate Megalocerus. The original spelling of Megalocerus was never used after its original publication.

Outdated 1897 reconstruction of doe and stag Irish elk by Joseph Smit

In 1844 Richard Owen named another synonym of the Irish elk, including it within the newly named subgenus Megaceros, Cervus (Megaceros) hibernicus. This has been suggested to be derived from another junior synonym of the Irish elk described by J. Hart in 1825, Cervus megaceros. Despite being a junior synonym, Megaloceros remained in obscurity and Megaceros became the common genus name for the taxon. The combination “Megaceros giganteus” was in use by 1871. George Gaylord Simpson in 1945 revived the original Megaloceros name, which became progressively more widely used, until a taxonomic decision in 1989 by the ICZN confirmed the priority of Megaloceros over Megaceros, and Megaloceros to be the correct spelling.

Before the 20th century, the Irish elk, having evolved from smaller ancestors with smaller antlers, was taken as a prime example of orthogenesis (directed evolution), an evolutionary mechanism opposed to Darwinian evolution in which the successive species within the lineage become increasingly modified in a single undeviating direction, evolution proceeding in a straight line void of natural selection. Orthogenesis was claimed to have caused an evolutionary trajectory towards antlers that became larger and larger, eventually causing the species’ extinction because the antlers grew to sizes which inhibited proper feeding habits and caused the animal to become trapped in tree branches. In the 1930s, orthogenesis was disputed by Darwinians led by Julian Huxley, who noted that antler size was not grossly large, and was proportional to body size. The currently favoured view is that sexual selection was the driving force behind the large antlers rather than orthogenesis or natural selection.

Outdated 1906 restoration by Charles R. Knight

Evolution

Skull of M. g. antecedens

M. giganteus belongs to the genus Megaloceros. Megaloceros is a member of the possibly polyphyletic (invalid) tribe “Megalocerini” or “Megacerini”, alongside Megaceroides, Praemegaceros, Eucladoceros and Sinomegaceros, which are often collectively referred to as “giant deer”. The taxonomy of giant deer lacks consensus, with genus names used for species varying substantially between authors. The earliest possible record of the genus is a partial antler from the Early Pleistocene MN 17 (2.5–1.8 Ma) of Stavropol Krai in the North Causcaus of Russia, which were given the name of M. stavropolensis in 2016, however these have been subsequently suggested to belong to Arvernoceros instead. The oldest generally accepted records of the genus are from the late Early Pleistocene. Other species often considered to belong to Megaloceros include the reindeer sized M. savini, which is known from early Middle Pleistocene (~700,000–450,000 years ago) localities in England, France, Spain and Germany, and the more recently described species M. novocarthaginiensis, which is known from late Early Pleistocene (0.9–0.8 Ma) localities in Spain, and the small M. matritensis endemic to the Iberian peninsula during the late Middle Pleistocene (~400,000 to 250,000 years ago), which overlaps chronologically with the earliest M. giganteus records. Jan van der Made proposed these species to be chronospecies, due to shared morphological characteristics not found in M. giganteus and gradual transition of morphological characters through time. M. savini has also been suggested to comprise the separate genus Praedama by some scholars, though they are often considered closely related. Roman Croitor has suggested closer affinities to Eucladoceros for M. savini and related species.

The origin of M. giganteus remains unclear, and appears to lie outside Western Europe. Jan van der Made has suggested that remains of an indeterminate Megaloceros species from the late Early Pleistocene (~1.2 Ma) of Libakos in Greece are closer to M. giganteus than the M. novocarthaginiensis-matritensis lineage due to the shared molarisation of the lower fourth premolar (P4). Croitor has suggested that M. giganteus is closely related to what was originally described as Dama clactoniana mugharensis (which he proposes be named Megaloceros mugharensis) from the Middle Pleistocene of Tabun Cave in Israel, due to similarities in the antlers, molars and premolars. The earliest possible records of M. giganteus comes from Homersfield, Norfolk, thought to be about 450,000 years ago—though the dating is uncertain. The oldest securely dated Middle Pleistocene records are those from Hoxne, which have been dated to MIS 11 (424,000 to 374,000 years ago), other Middle Pleistocene early records include Steinheim an der Murr, Germany, (classified as M. g. antecedens) about 400,000–300,000 years ago and Swanscombe. Most remains of the Irish elk are known from the Late Pleistocene. A large proportion of the known remains of M. giganteus are from Ireland, which mostly date to the Allerød oscillation near the end of the Late Pleistocene around 13,000 years ago. Over 100 individuals have been found in Ballybetagh Bog near Dublin.

It has been historically thought that, because both have palmated antlers, the Irish elk and fallow deer (Dama spp.) are closely related, this is supported by several other morphological similarities, including the lack of upper canines, proportionally long braincase and nasal bones, and proportionally short front portion of the skull. In 2005, two fragments of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from the cytochrome b gene were extracted and sequenced from 4 antlers and a bone, the mtDNA found that the Irish Elk was nested within Cervus, and were inside the clade containing living red deer (Cervus elaphus). Based on this, the authors suggested that the Irish elk and red deer interbred, which would be unsurprising as hybridisation is known to occur among present-day deer species. However, another study from the same year in Nature utilising both fragmentary Mitochondrial DNA and morphological data found that the Irish Elk was indeed most closely related to Dama. The close relationship with Dama was supported by another cytochrome b study in 2006, a 2015 study involving the full mitochondrial genome, and by a 2017 morphological analysis of the bony labyrinth. The 2006 and 2017 studies also directly suggest that the results of the 2005 cytochrome b paper were the result of DNA contamination.

Description

Restoration

Drawing of cave art from Grotte de Cougnac, France showing coloured shoulder hump and lines. c. 25,000 to 19,000 years old

The Irish elk stood about 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in) tall at the shoulders and carried the largest antlers of any known deer, a maximum of 3.65 m (12.0 ft) from tip to tip and 40 kg (88 lb) in weight. For body size, at about 450–600 kg (990–1,300 lb) and up to 700 kg (1,500 lb) or more, the Irish elk was the heaviest known cervine (“Old World deer”) and tied with the extant Alaska moose (Alces alces gigas) as the third largest known deer, after the extinct Cervalces latifrons and Cervalces scotti. Nonetheless, compared to Alces, Irish elk appear to have had a more robust skeleton, with older and more mature Alces skeletons bearing some resemblance to those of prime Irish elk, and younger Irish elk resembling prime Alces. Likely due to different social structures, the Irish elk exhibits more marked sexual dimorphism than Alces, with Irish elk bucks being notably larger than does. In total, Irish elk bucks may have ranged from 450–700 kg (990–1,540 lb), with an average of 575 kg (1,268 lb), and does may have been relatively large, about 80% of buck size, or 460 kg (1,010 lb) on average. The distinguishing characters of M. giganteus include concave frontals, proportionally long braincase, proportionally short front section of the skull (orbitofrontal region), alongside the absence of upper canines and the molarisation of the lower fourth premolar (P4). The skull and mandible of the Irish elk exhibit substantial thickening (pachyostosis), with the early and complete obliteration of cranial sutures.

One of our long standing committee members and humane dispatch team members responding to a call out earlyer this morning , it was on arrival that the best option was to set free this young fallow buck as it showed no signs of injury . Well done to all in a succesfull release .

#setfree #irishfallowbuck #irishhuntingpodcast #notalwaysaboutpullingthetrigger

Based on Upper Palaeolithic cave paintings, the Irish elk seems to have had overall light colouration, with a dark stripe running along the back, a stripe on either side from shoulder to haunch, a dark collar on the throat and a chinstrap, and a dark hump on the withers (between the shoulder blades). In 1989, American palaeontologist Dale Guthrie suggested that, like bison, the hump allowed a higher hinging action of the front legs to increase stride length while running. Valerius Geist suggested that the hump may have also been used to store fat. Localising fat rather than evenly distributing it may have prevented overheating while running or in rut during the summer.

Habitat

Neither exclusive to Ireland nor an elk, it was named so because the most well-known and best-preserved fossil specimens have been found in lake sediments and peat bogs in Ireland. The Irish elk had a far-reaching range, extending from the Atlantic Ocean in the West to Lake Baikal in the East. They do not appear to have extended northward onto the open mammoth steppe, rather keeping to the boreal steppe-woodland environments, which consisted of scattered spruce and pine, as well as low-lying herbs and shrubs including grasses, sedges, Ephedra, Artemisia and Chenopodiaceae.

Irish elk mount at the American Museum of Natural History, New York

36,000 year old Irish elk cave painting at Chauvet Cave, France (dot indicates 14C sample)

Palaeobiology

Physiology

In 1998, Canadian biologist Valerius Geist hypothesised that the Irish elk was cursorial (adapted for running and stamina). He noted that the Irish elk physically resembled reindeer, and the body proportions of the Irish elk are similar to those of the cursorial addax, oryx, and saiga antelope. These include the relatively short legs, the long front legs nearly as long as the hind legs, and a robust and cylindrical body. Cursorial saiga, gnus, and reindeer have a top speed of over 80 km/h (50 mph), and can maintain high speeds for up to 15 minutes.

Reproduction

At Ballybetagh Bog, over 100 Irish elk individuals were found, all small antlered bucks. This indicates that bucks and does segregated during at least winter and spring. Many modern deer species do this in part because males and females have different nutritional requirements and need to consume different types of plants. Segregation would also imply a polygynous society, with stags fighting for control over harems during rut. Because most of the individuals found were juvenile or geriatric and were likely suffering from malnutrition, they probably died from winterkill. It is possible that most Irish elk specimens known had died from winterkill, and winterkill is the highest source of mortality among many modern deer species. Bucks generally suffer higher mortality rates because they eat little during the autumn rut. For rut, a lean stag normally 575 kg (1,268 lb) may have fattened up to 690 kg (1,520 lb), and would burn through the extra fat over the next month.

Assuming a similar response to starvation as red deer, a large, healthy Irish elk stag with 40 kg (88 lb) antlers would have had 20-to-28 kg (44-to-62 lb) antlers under poor conditions and an average sized Irish elk stag with 35 kg (77 lb) antlers would have had 18 to 25 kg (40 to 55 lb) antlers under poorer conditions, similar sizes to the moose. A similar change in a typical Irish elk population with prime stags having 35 kg (77 lb) antlers would result in antler weights of 13 kg (29 lb) or less in worsening climatic conditions. This is within the range of present day wapiti/red deer (Cervus spp.) antler weights. Irish elk antlers vary widely in form depending upon the habitat, such as a compact, upright shape in closed forest environments. Irish elk likely shed their antlers and re-grew a new pair during mating season. Antlers generally require high amounts of calcium and phosphate, especially those for stags which have larger structures, and the massive antlers of Irish elk may have required much greater quantities. Stags typically meet these requirements in part from their bones, suffering from a condition similar to osteoperosis while the antlers are growing, and replenishing them from food plants after the antlers have grown in or reclaiming nutrients from shed antlers.

The large antlers have generally been explained as being used for male-male battle during mating season. They may have also been used for display, to attract females and assert dominance against rival males. A finite element analysis of the antlers suggested that during fighting, the antlers were likely to interlock around the middle tine, the high stress when interlocking on the distal tine suggests that the fighting was likely more constrained and predictable than among extant deer, likely involving twisting motions, as is known in extant deer with palmated antlers.

In deer, gestation time generally increases with body size. A 460 kg (1,010 lb) doe may have had a gestation period of about 274 days. Based on this and patterns seen in modern deer, last year’s antlers in Irish elk bucks were potentially shed in early March, peak antler growth in early June, completion by mid-July, shedding velvet (a layer of blood vessels on the antlers in-use while growing them) by late July, and the height of rut falling on the second week of August. Geist, believing the Irish elk to have been a cursorial animal, concluded that a doe would have to have produced nutrient-rich milk so that her calf would have enough energy and stamina to keep up with the herd.

Life history

The mesodont (meaning neither high (hypsodont) or low (brachydont) crowned) condition of the teeth suggests that the species was a mixed feeder, being able to both browse and graze. Pollen remains from teeth found in the North Sea around 43 kya were found to be dominated by Artemisia and other Asteraceae, with minor Plantago, Helianthemum, Plumbaginaceae and Salix. A stable isotope analysis of the terminal Pleistocene Irish population suggests a grass and forb based diet, supplemented by browsing during stressed periods. Dental wear patterns of specimens from the late Middle and Late Pleistocene of Britain suggest a diet tending towards mixed feeding and grazing, but with a wide range including leaf browsing.

Based on the dietary requirements of red deer, a 675 kg (1,488 lb) lean Irish elk stag would have needed to consume 39.7 kg (88 lb) of fresh forage daily. Assuming antler growth occurred over a span of 120 days, a stag would have required 1,372 g of protein daily, as well as access to nutrient- and mineral-dense forage starting about a month before antlers began sprouting and continuing until they had fully grown. Such forage is not very common, and stags perhaps sought after aquatic plants in lakes. After antler growing, stags could probably satisfy their nutritional requirements in productive sedge lands bordered by willow and birch forests.

The Irish elk may have been preyed upon by the large carnivores of the time, including the cave lion, and the cave hyena.

Extinction

Sculptures in Crystal Palace

Lister and Stewart note that “With the exception of the Irish late-glacial, finds of M. giganteus, throughout its Pleistocene history, are generally low in abundance at sites where they occur, suggesting that it was generally a rare species.

Historically, the extinction of the elk has been attributed to the encumbering size of the antlers, a “maladaptation” making fleeing through forests especially difficult for males while being chased by human hunters, or being too taxing nutritionally when the vegetation makeup shifted. In these scenarios, sexual selection by does for stags with large antlers would have contributed to decline.

However, antler size decreases through the Late Pleistocene and into the Holocene, and so may not have been the primary cause of extinction. A reduction in forest density in the Late Pleistocene and a lack of sufficient high-quality forage is associated with a decrease in body and antler size. Such resource constriction may have cut female fertility rates in half. Human hunting may have forced Irish elk into suboptimal feeding grounds.

The range of the taxon appears to have collapsed during the Last Glacial Maximum, with few remains known between 27.5 and 14.6 kya, and none between 23.3 and 17.5 kya. The remains of the taxon substantially increase during the latest Pleistocene, where it appears to have re-colonised most of its former range, with abundant remains in the UK, Ireland and Germany.

While the range of the taxon was dramatically reduced after the Pleistocene-Holocene transition, it managed to survive into the early Northgrippian in the eastern part of its range within European Russia and Siberia, in a belt extending from Maloarchangelsk in the East to Preobrazhenka in the west. It is suggested that extinction was contributed to by further climatic changes transforming preferred open habitat into uninhabitable dense forest. The final demise may have been caused by a number of factors both on a continental and regional scale, including climate change and hunting.

Lister and Stewart concluded in a study of the extinction of the Irish elk that “it seems clear that environmental factors, cumulatively over thousands of years, reduced giant deer populations to a highly vulnerable state. In this situation, even relatively low-level hunting by small human populations could have contributed to its extinction.

Cultural significance

Cave painting from Lascaux, c. 15,000 BC

A handful of Irish elk depictions are known from the art of the Upper Paleolithic in Europe, but these are much less abundant than the common red deer and reindeer depictions. The bones of the Irish elk are uncommon in localities were they are found, and only a handful of examples of human interaction are known. A mandible from Ofatinţi, Moldova dating to either the Eemian or the early Late Pleistocene, “is peculiar because it has ancient tool-made notches on its lateral side”. Several M. giganteus bones from the Chatelperronian levels of the Labeko Koba site in Spain are noted for bearing puncture marks, which have been interpreted as anthropogenic. A terminal Pleistocene (13710-13215 cal BP) skull from Lüdersdorf, Germany is noted to have had the antler and facial part of the skull removed in a way unlikely to be due to natural causes. A calcaneum from an associated lower hind limb from the early Holocene site of Sosnovy Tushamsky in Siberia is noted to have “two short and deep traces of cutting blows”, which are interpreted as “clear evidence of butchery”. The use of shed antler bases is also known, at the terminal Pleistocene (Allerød) Endingen VI site in Germany, a shed antler base appears to have been used in a way analogous to a lithic core to produce “blanks” for the manufacture of barbed projectile tips. A ring like mark on a shed antler beam from the similarly aged Paderborn site in Germany has been suggested to be anthropogenic.

Due to the abundance of Irish elk remains in Ireland, a thriving trade in their bones existed there during the 19th century to supply museums and collectors. Skeletons and skulls with attached antlers were also prized ornaments in aristocratic homes. The remains of Irish elk were of high value: “In 1865, full skeletons might fetch £30, while particularly good heads with antlers could cost £15.” with £15 being more than 30 weeks wages for a low skilled worker at the time.

A folk memory of the Irish elk was once thought to be preserved in the Middle High German word Schelch, a large beast mentioned in the 13th-century Nibelungenlied along with the then-extant aurochs (Dar nach schluch er schiere, einen Wisent und einen Elch, Starcher Ure vier, und einen grimmen Schelch / “After this he straightway slew a Bison and an Elk, Of the strong Wild Oxen four, and a single fierce Schelch.”) This opinion is no longer widely held. The Middle Irish word segh was also suggested as a reference to the Irish elk. Turf cutters of Clooney and Tulla in County Clare, Ireland referred to the Irish elk as the Fiaghmore. However, these interpretations are not conclusive.

(txt takin from Wikipedia)